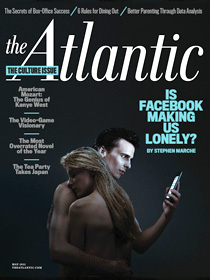

L’article qui fait la couverture du magazine The Atlantic de mai 2012 traite des exigences de la culture du paraître à la base des réseaux sociaux et du sentiment de solitude qui en découle parfois. Il a suscité de nombreuses réactions. Tant que Facebook, Twitter et consorts permettent de développer de nouveaux liens en présentiel, ils sont de puissants outils. Lorsqu’ils remplacent les contacts réels par des liens virtuelles et artificiels, on doit se questionner. Est-ce que la profondeur de telles interrogations pourrait militer en faveur d’un apprivoisement des réseaux sociaux au niveau universitaire, avec le recul critique que cela nécessite ?

L’article qui fait la couverture du magazine The Atlantic de mai 2012 traite des exigences de la culture du paraître à la base des réseaux sociaux et du sentiment de solitude qui en découle parfois. Il a suscité de nombreuses réactions. Tant que Facebook, Twitter et consorts permettent de développer de nouveaux liens en présentiel, ils sont de puissants outils. Lorsqu’ils remplacent les contacts réels par des liens virtuelles et artificiels, on doit se questionner. Est-ce que la profondeur de telles interrogations pourrait militer en faveur d’un apprivoisement des réseaux sociaux au niveau universitaire, avec le recul critique que cela nécessite ?

Quelques extraits parlant :

«Our omnipresent new technologies lure us toward increasingly superficial connections at exactly the same moment that they make avoiding the mess of human interaction easy. The beauty of Facebook, the source of its power, is that it enables us to be social while sparing us the embarrassing reality of society—the accidental revelations we make at parties, the awkward pauses, the farting and the spilled drinks and the general gaucherie of face-to-face contact. Instead, we have the lovely smoothness of a seemingly social machine. Everything’s so simple: status updates, pictures, your wall. »

« …[L]oneliness and narcissism are intimately connected: a longitudinal study of Swedish women demonstrated a strong link between levels of narcissism in youth and levels of loneliness in old age. The connection is fundamental. Narcissism is the flip side of loneliness, and either condition is a fighting retreat from the messy reality of other people.

[…] What’s truly staggering about Facebook usage is not its volume—750 million photographs uploaded over a single weekend—but the constancy of the performance it demands. More than half its users—and one of every 13 people on Earth is a Facebook user—log on every day. Among 18-to-34-year-olds, nearly half check Facebook minutes after waking up, and 28 percent do so before getting out of bed. The relentlessness is what is so new, so potentially transformative. Facebook never takes a break. We never take a break. Human beings have always created elaborate acts of self-presentation. But not all the time, not every morning, before we even pour a cup of coffee. […].…What Facebook has revealed about human nature—and this is not a minor revelation—is that a connection is not the same thing as a bond, and that instant and total connection is no salvation, no ticket to a happier, better world or a more liberated version of humanity. Solitude used to be good for self-reflection and self-reinvention. But now we are left thinking about who we are all the time, without ever really thinking about who we are. Facebook denies us a pleasure whose profundity we had underestimated: the chance to forget about ourselves for a while, the chance to disconnect. » [nos emphases]

Sources :

Lagacé, Patrick, « Pourquoi suis-je fasciné par cette couverture du Atlantic ? », Cyberpresse.ca, 13 avril 2012.

Marche, Stephen, « Is Facebook Making Us Lonely ? », The Atlantic, Mai 2012.

Dans le magazine Slate, Eric Klinenberg réfute une bonne part des arguments et des sources de Marche. Est-ce que les questions que soulèvent Marche en sont moins pertinentes pour autant ? Je ne le crois pas.

Klinenberg, Eric, « Facebook Isn’t Making Us Lonely », Slate, 19 avril 2012